How Chopsticks Are Made

Did you ever wonder how chopsticks are made? The manufacturing processes are quite amazing. In this article we'll explore how many different kinds of chopsticks are made, from cheap disposable chopsticks, to everyday use chopsticks, to the finest styles of craftsmanship such as Washi Paper Wrapped, Nishi-jin and perhaps the best of all - Wakasa.

Contents:

How Everyday Use Chopsticks Are Made

There

are many forms of chopsticks from simple disposable chopsticks to

handcrafted chopsticks using centuries-old techniques. The most common

non-disposable chopstick is what we call the everyday chopstick. This is

what you find in most gift shops and Asian grocery stores. They are

durable, come in an endless array of colors and designs, and cost just a

few dollars. Here we'll describe the production process for the

manufacture of everyday chopsticks.

The

core of the chopstick is made of either wood or bamboo. Bamboo is

slightly less expensive and perhaps a more renewable resource, but can

be a little more prone to warping. Wood chopsticks are made from wood

varieties similar to alder.

The wood is cut or split into lengths

about 1-1/2 times the length of one chopstick. This wood blank will make

one chopstick with room in the middle for handling during the finish

process. The blank is milled down to the final shape of the chopstick

and sanded smooth in preparation for the painting process.

Virtually

all chopsticks are made to order from the factory. Base wood, length,

thickness, tip thickness and style, finish design and quality, and final

packaging are all specified prior to production. Typically a buyer must

order between 5,000 to 10,000 of each color and style from the factory.

Therefore

there are differences in quality from one seller's chopsticks to the

next depending on the quality of finish and packaging. For instance

chopsticks produced for the domestic Chinese market tend to have 1-3

layers of paint finish while chopsticks for the Japanese and United

States usually have 4-5 layers, making for a richer, deeper-colored and

more durable final look, and are called "Japanese #1" style.

The

first 2 layers of the Japanese #1 style chopstick are a primer or

sealer. Between each coat the primer is sanded smooth. Clear lacquered

chopsticks do not use a primer. Then 2 coats of the color layer are

applied to form a rich, deep color.

At

this point many chopsticks receive a design, typically on the handle.

Although sometimes this decoration or design is hand painted, almost all

chopsticks have applied a decal-like pre-printed layer. This decal is

called a heat stamp and is sometimes applied at a different factory that

specializes in making and applying the heat stamps.

Once the heat

stamp is applied, a final clear coat finish is applied to seal the body

of the chopstick. During this entire process the stick has retained an

extra length for holding the stick while painting and finishing. Once

the body is finished the end is trimmed and finished by dipping or

painting, sometimes in a contrasting color.

Next,

chopsticks are joined into pairs with a sticker wrap at their middle.

The sticks are generally carefully aligned so their design continues

across both sticks. Then the chopsticks are typically inserted into a

clear plastic sealed envelope, referred to as an "OPP bag". This

protects the chopsticks and keeps them clean while on display at the

store and while in storage. Finally the chopsticks are bundled into bags

of 100 pairs or boxes of 50 pairs, and packed in master cases of

usually 1000 pairs for easy handling and distribution.

This entire

process typically takes about 45 days to allow proper drying of each

paint layer. Remarkably the finish process is mostly done by hand as you

can see in the attached photos from one of China's largest chopstick

factories. This is in stark contrast to disposable chopsticks which are

machine stamped and milled entirely.

Back to Top

All About Washi Paper Wrapped Chopsticks

Beautiful Washi Paper Wrapped Chopsticks

Beautiful Washi Paper Wrapped Chopsticks

Washi chopsticks are fine handcrafted Japanese chopsticks with handmade decorative washi paper laminated around the chopstick handles. This method of decorating chopstick handles with an application of a "design" or "decal" of sorts is perhaps the earliest predecessor to modern mass-produced heat stamp designs common on all inexpensive chopsticks produced in China today.

Washi

is the Japanese traditional craft of hand-making paper, dating back

more than 1,000 years. Like manufacturing fine chopsticks, the making of washi has dwindled in the last hundred years with the advent of modern machinery and westernized utilitarian papers. Where there were over 100,000 families making washi in the 1800's, there are fewer than 350 remaining today.

Although washi can be made as a plain paper, the fine craft of washi produces some of the most ornate and decorative papers, which is what's used on chopsticks.

Washi is made primarily of three fibers - Kozo (mulberry), Mitsumata and Gampi. Other fibers such as hemp, abaca, horsehair, rayon, gold and

silver foils are added for decorative effect. The plants are soaked,

bark removed, and then pounded and stretched. The fiber is then mixed

with fermented hibiscus root to form a fibrous paste that is then spread thin over bamboo screens and set to dry.

The center of washi production is in Kyoto, Japan, close to Obama, Japan where 80% of all Japanese chopsticks are made. Thus the natural combination of washi and chopstick. Washi has been used in making shoji screens and even money, as well as for writing papers, wrapping paper, packaging, origami, and art prints.

Back to Top

The Alure of Nishijin Chopsticks

In Japan, about 80% of chopsticks are manufactured in Obama city in the Fukui prefecture. About 45 miles east lies Kyoto prefecture, one of Japan's most traditional cities and the home of many traditional crafts.

Among these, Nishijin ori is widely regarded as one of the nation's

foremost achievements in any craft.

The

history of Nishijin ori - silk cloth produced in the Nishijin district

of Kyoto - goes back to the sixth century, when silk farming and silk

weaving were introduced in the western part of Kyoto by the Hata family, who may have originated from China. The Heian period saw the formation of an official weaver's guild, but civil strife during the eleven years of the Onin Wars (1467-77) laid Kyoto to waste. Some weavers fled to the port town of Sakai, where they studied Ming weaving techniques.

When calm was restored to Kyoto, the weavers returned. Some settled in the

eastern part of Kyoto known as Tojin, and began weaving habutae, a

lightweight plain-weave cloth, and nerinuki, a cloth using raw silk and

glossed-silk thread. Other weavers who settled in western Kyoto, an

sector called Nishijin, focused on twilled cloths, the foundation of

today's Nishijin ori. In the nineteenth century a delegation of Nishijin

weavers traveled to Europe to learn European methods of weaving

Jacquard and integrated Jacquard techniques into their weaving back in

Japan.

Woven

fabric production in Nishijin has spurred many varieties and forms,

including the tightly woven tsuzure, the brocade nishiki, yarn-dyed

tatenishiki, nikinishiki, donsu, shuchin, shoha and futsu.

The

cloths produced in Nishijin have earned international renown, reflecting

an endless wealth of designs and techniques. Obi and kimono fabrics are

still being made as they were in the past. The variety is as great as

the artistry and technique are brilliant.

With

the close proximity of Kyoto to Obama, the natural combination of

Nishijin fabrics applied to fine chopsticks evolved.

Each pair of chopsticks features a style and pattern of Nishijin ori

fabric wrapped perfectly to black wooden chopsticks. The fabric is

sealed for protection from food and water stains that makes for a very

durable yet artistic pair of chopsticks. Each pair is a true work of art

and presents a truly unique presentation at the dinner table. See our

complete selection of Nishijin chopsticks and enjoy their beautiful artistry.

Back to Top

Amazing Wakasa Chopsticks

Wakasa Daikan

Wakasa Daikan

We have a one of the largest collections of Wakasa chopsticks. Wakasa chopsticks are one of the most special forms of chopstick hand craftsmanship, with family shops passing down their unique techniques and designs from father to son for centuries.

Wakasa is a dying art in Japan. Hundreds of families made Wakasa lacquer ware in the 1800's. Today the craft is maintained by 9 firms employing fewer than 40 craftsmen in the city of Obama, Japan. In the modern era children are less likely to follow in their family businesses.

The name Wakasa comes from where they are made and what their designs represent. The designs represent views through the crystal clear waters of Wakasa bay. The name for the city of Obama originates from the Obama clan that inhabited the area, who were famous for their lacquerware products. This small city of less than 33,000 people produces 80% of all chopsticks made in Japan.

Craftsmen use all natural materials to represent scenes of the ocean floor below. Mother-of-pearl, eggshell, gold and silver leaf are used to depict marine elements. Elegant Wakasa chopsticks have been made in Fukui prefecture, Japan since the Edo period (1603-1868).

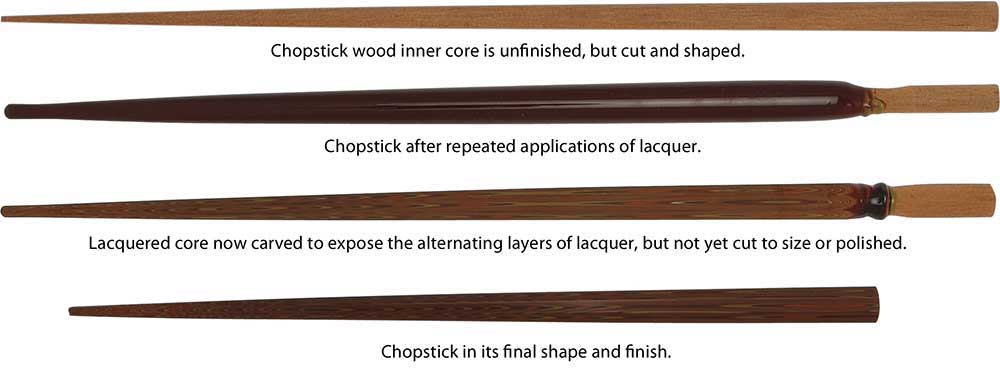

Steps in making Wakasa chopsticks

Steps in making Wakasa chopsticks

The production of Wakasa lacquer ware chopsticks can involve over 50 processes. After careful preparation and sealing of the base cherry wood chopstick a number of layers of lacquer are applied and rubbed down between each one. Each layer requires time to air harden. The application of shell, gold leaf and pine needles combined with the repeated coating and rubbing down of the lacquer layers creates the famous unusual and random decoration. Carving also determines the final shape and look of the chopstick.

A single pair of Wakasa chopsticks can take many months to complete. Because of the time, experience and hand labor required Wakasa chopsticks are more costly. Despite their cost these chopsticks are meant to be used and not stored away on display.

Each craftsman has his own unique style. Therefore Wakasa chopsticks come in many beautiful designs, patterns and finishes. Each pair is a work of art.

Wakasa Ren Fune

Wakasa Ren Fune